Table of Contents

Reflecting on South Korea’s journey, you feel empathy for its people. The country faced many periods of martial law since its founding in 1948. Each period showed how fragile democracy is and how the military can influence a nation’s path1.

Just two months after its founding, South Korea saw its first martial law. President Syngman Rhee tried to stop communist uprisings, leading to thousands of deaths1. The military’s control grew during the Korean War, allowing it to silence protests1.

In 1960, Rhee’s government imposed martial law again, sparking violent clashes that killed hundreds1. The people’s desire for freedom never faded.

President Park Chung-hee declared martial law in 1972 to suppress dissent. His rule was marked by protests and political imprisonment1. Even after Park’s death, the military kept a tight grip on power.

In 1979, President Choi Kyu-hah used martial law to maintain his government. Mass protests led to nearly a thousand deaths and his resignation1.

The most brutal chapter of martial law in South Korea happened in 1980. General Chun Doo-Hwan extended the state of emergency after a coup. He used force to silence student protests in Gwangju, killing hundreds1. Martial law was lifted in 1981, marking a move towards democracy1.

Key Takeaways

- South Korea faced many martial law periods from 1948 to 1981, often due to political unrest and protests.

- Martial law was used to suppress dissent and maintain power, causing violence and imprisonment.

- The 1980 martial law led to the Gwangju Uprising, where hundreds were killed by the military.

- The 1981 lifting of martial law was a key step towards democracy in South Korea, but challenges remained.

- The martial law history in South Korea shows democracy’s fragility and the military’s influence on a nation’s politics.

The Origins of Martial Law in Post-War South Korea

After World War II, South Korea became an independent nation in 1948. It faced political instability and threats from communist uprisings2. President Syngman Rhee quickly used martial law to control these threats3.

First Implementation Under President Syngman Rhee

In 1948, just two months after South Korea’s founding, martial law was first used3. Rhee used it to fight communist insurgents, causing thousands of deaths. This set a bad example for future use of martial law3.

Communist Uprisings and Government Response

After South Korea’s independence, there were many protests and tensions with North Korea3. Rhee’s tough response to communist uprisings, including martial law, started a long period of authoritarian rule3.

Early Political Instability

The early years of South Korea’s government were very unstable3. Rhee’s use of martial law to silence dissent set the stage for future conflicts with the south korean democracy movement2.

| Event | Year | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Martial law first imposed by President Syngman Rhee | 1948 | Thousands of deaths in suppressing communist uprisings |

| Martial law invoked during Korean War | 1950-1953 | Used to quell anti-government protests |

| Martial law imposed by President Syngman Rhee | 1960 | Hundreds killed in clashes between protesters and police |

South Korea Under Martial Law During the Korean War (1950-1953)

From 1950 to 1953, South Korea was under martial law4. This gave the government the power to stop protests and fight North Korea. Martial law was a way to keep control inside the country while facing threats from outside.

The Korean War was a big moment in Korea’s history4. South Korea used martial law to stop any opposition during the war4.

Martial law helped South Korea control any communist movements or challenges to its rule4. But, it also hurt democracy and made military rule stronger.

The effects of martial law during the Korean War are still seen today in South Korea4. This period shows how fragile democracy can be and the risks of too much military power.

| Statistic | Value |

|---|---|

| Last time martial law was imposed in South Korea | Nearly half a century ago in 1979, amid a period of authoritarian rule that ended in 19874. |

| Period of military junta in South Korea after the Korean War | Dictatorial leaders occasionally declared martial law to suppress anti-government protests4. |

| National Assembly vote to end martial law | Unanimous 190-0, occurring six hours after President Yoon Suk-yeol imposed it4. |

| President Yoon Suk-yeol’s approval rating before the imposition of martial law | A lowly 20%, facing calls for impeachment4. |

| Opposition parties’ motion to impeach President Yoon after the imposition of martial law | Requires the support of two-thirds of the parliament and at least six Constitutional Court judges4. |

| Probability of impeachment for President Yoon | Seems to be the most probable outcome based on the almost unanimous condemnation of his actions, including within his own party4. |

The 1960 Crisis and Democratic Uprising

In 1960, President Syngman Rhee faced growing opposition and declared martial law5. Hundreds died in clashes between protesters and police6. South Korea has seen military rule many times, with martial law imposed often5.

Student-Led Protests Against Rhee’s Government

Students led the charge, throwing rocks and shouting slogans despite government bans6. Martial law’s last use in South Korea was in the late 1970s. This is a time most young people don’t remember5.

Nationwide Demonstrations and Rhee’s Resignation

The protests grew across the country, leading to Rhee’s resignation6. South Korea’s democracy started in 1988, ending nearly three decades of dictatorship5.

Aftermath and Political Changes

After Rhee left office, South Koreans celebrated by climbing tanks outside Seoul’s City Hall6. The Korean War, starting in 1950, lasted three years and killed about two million people5.

The 1960 south korean uprising and syngman rhee resignation were key moments in South Korea’s fight for democracy. Student protests against the government led to Rhee’s downfall56.

Park Chung-hee’s Military Dictatorship (1961-1979)

In 1961, Park Chung-hee, a military general, took power in a coup d’état7. His rule lasted nearly 20 years, the longest martial law period in South Korea8. He staged another coup in 1972, declaring martial law and using tanks in Seoul’s streets7.

Even after lifting martial law in 1972, protests against his rule grew8. Yet, his economic reforms made South Korea’s economy soar, earning it the “Miracle on the Han River” nickname7. Big companies like Hyundai, LG, and Samsung rose to global fame7.

Park Chung-hee’s legacy is both celebrated and criticized. His economic growth was impressive, but his regime was known for harsh tactics, including torture and killings8. After his death in 1979, South Korea saw more protests and a slow move towards democracy8.

Today, opinions on Park Chung-hee vary in South Korea. A 2021 Gallup Korea poll showed he was seen positively by many7. Yet, the effects of martial law on South Korea’s politics and society are still debated8.

The Yushin Constitution and Emergency Measures

From 1972 until his death in 1979, former President Park Chung-hee used emergency laws to silence critics in South Korea9. These laws, part of the Yushin Constitution, gave Park almost total control. He used them to jail hundreds of political opponents and activists9. This time was marked by harsh crackdowns on dissent and many human rights violations, making people even more opposed to Park’s rule9.

Implementation of Dictatorial Powers

The Yushin Constitution, introduced in 1972, made Park the de facto dictator of South Korea9. Park used this power to declare martial law several times, shutting down democracy and silencing opposition9. He banned political gatherings, protests, and controlled the media and books9.

Suppression of Political Dissent

The government’s crackdown on dissent grew stronger, with many activists, students, and opposition leaders jailed9. Actions seen as threats to order were banned, and the military enforced these rules9. Army Chief of Staff Park An-soo was in charge of these actions9.

The impact of the Yushin Constitution and Park’s emergency laws still affects South Korea today10911. It warns of the risks of unchecked power10911.

The 1979 Assassination and Political Transition

On October 26, 1979, South Korea was shocked by the death of President Park Chung-hee12. Prime Minister Choi Kyu-hah then declared martial law to keep power12. Choi wanted to rule as a civilian but used martial law to stay in control12.

After Park’s death, protests and unrest spread, with 987 reported deaths12. This showed how fragile South Korea’s politics were at the time12.

The country was in a tough spot after Park’s death. Martial law was used to keep order but also sparked more unrest and calls for democracy12.

The turmoil of 1979 had lasting effects. It led South Korea towards democracy and a more stable future12.

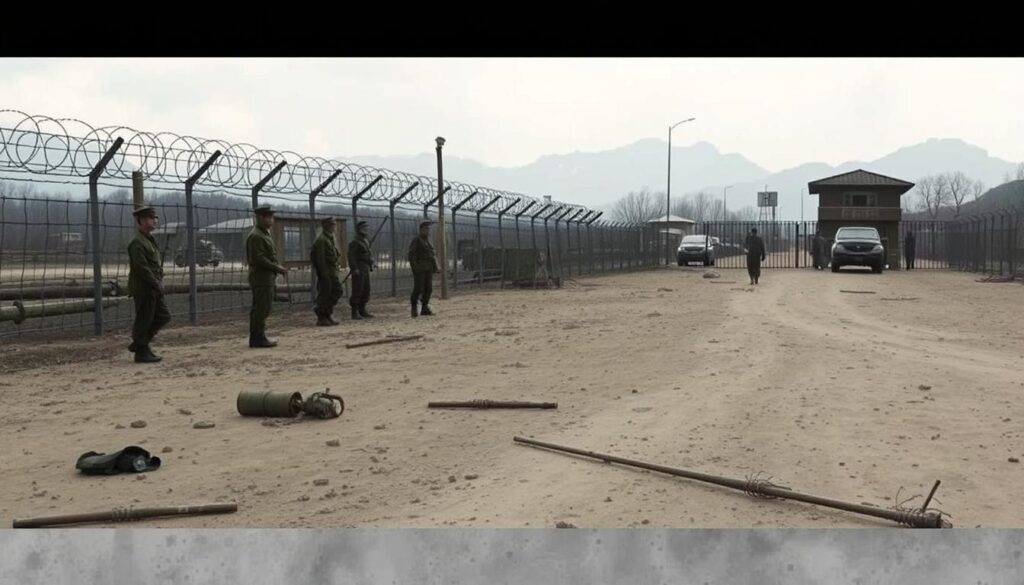

The Gwangju Uprising and Military Response

In 1980, South Korea was in chaos. General Chun Doo-hwan took over the presidency through a military coup. He also extended martial law across the country13. This was the 17th time martial law was declared in Korea, with the last time being in the 1980s after Park Chung-hee’s assassination13.

Student Demonstrations and Civil Unrest

The Chun regime’s strict rule led to student protests in Gwangju. Citizens fought against the authoritarian rule14. At least 200 people died during the military’s crackdown on the pro-democracy uprising, known as the Gwangju Massacre14.

The protesters, armed with stolen police and military weapons, clashed fiercely with government forces. This was a key moment in South Korea’s fight for democracy14.

Military Intervention and Civilian Casualties

The Chun Doo-hwan military junta used brutal force to stop the Gwangju Uprising. They sent troops and tanks to crush the civilian resistance14. This crackdown led to hundreds of civilian deaths, a dark time in South Korea’s history14.

The 1980 Gwangju Uprising was a powerful symbol against authoritarian rule. It was a key event that led to South Korea’s transition to democracy in the late 1980s14.

| Key Events | Impact |

|---|---|

| 1980 Gwangju Uprising | Student-led protests against the Chun Doo-hwan military junta, resulting in hundreds of civilian casualties during the military crackdown. |

| Gwangju Massacre | A tragic event where the military used excessive force to suppress the pro-democracy demonstrations, becoming a pivotal moment in South Korea’s history. |

| Transition to Democracy | The Gwangju Uprising and the subsequent events contributed to the eventual transition of South Korea from military rule to a democratic system in the late 1980s. |

The Path to Democracy: Transitioning from Military Rule

After the Gwangju Uprising, protests against military rule grew stronger in South Korea. Thousands of university students in Seoul demanded an end to martial law, facing tear gas from riot police15. Martial law was lifted in 1981, showing a move away from military control15.

The fight for south korean democracy movement went on through the 1980s. The start of the sixth republic in 1988 marked South Korea’s move to a full democracy15. This ended the frequent end of martial law declarations.

The path to democracy in South Korea was filled with challenges and sacrifices. Student-led protests and civil unrest were key in pushing the military to give up power15. The journey was tough, but the South Korean people’s resilience and determination led to a stable democracy.

Today, South Korea is a vibrant and thriving democracy. It shows the lasting spirit of its citizens who fought for their political freedoms15. The south korean democracy movement is an inspiring example of collective action shaping a nation’s history.

| Key Milestones in South Korea’s Democratic Transition | Year |

|---|---|

| Martial law lifted, signaling a shift away from military rule | 1981 |

| Establishment of the Sixth Republic, marking South Korea’s transition to a fully functioning democracy | 1988 |

| South Korea has been a democracy since | 1987 |

The journey to democracy in South Korea was not easy. The south korean democracy movement faced strong opposition from the military regime16. But the people’s determination and international pressure led to the end of martial law and the sixth republic.

Today, South Korea is a beacon of a successful transition from military rule to democracy. The lessons from this journey inspire and guide democratic movements worldwide.

Conclusion

South Korea’s history with martial law, from 1948 to 1981, has deeply influenced its politics17. This period saw 16 martial law declarations to fight communist uprisings and keep control17. The 1980 Gwangju Uprising was a turning point, sparking the democracy movement and leading to democratic rule in 1988.

The impact of martial law still affects South Korea’s memory and politics18. President Yoon Suk Yeol’s recent martial law declaration was quickly overturned due to public and National Assembly opposition18. This shows how sensitive the country is to such measures.

The shift from authoritarian rule to democracy has been tough, but the people’s strength has been key17. The government’s low approval ratings and the opposition’s impeachment efforts highlight ongoing debates about democracy’s future17.

FAQ

What was the history of martial law in South Korea?

South Korea saw martial law from 1948 to 1981. It was used during political crises, uprisings, and war. The first time was in 1948 to fight communist uprisings. Martial law was also used during the Korean War and in 1960 and 1979-1981 to keep power.

How did martial law originate in South Korea?

Martial law started in 1948, just two months after South Korea was founded. President Syngman Rhee used it to stop communist uprisings, leading to thousands of deaths. This set a pattern for future use to control politics.

How was martial law used during the Korean War?

From 1950 to 1953, martial law was in place during the Korean War. It allowed the South Korean government to control protests while fighting North Korea. This made authoritarian measures common in crises.

What was the role of martial law in the 1960 crisis and democratic uprising?

In 1960, President Syngman Rhee faced opposition and declared martial law again. Hundreds died in clashes between protesters and police. This forced Rhee to step down, a key moment for South Korea’s democracy.

How did martial law impact Park Chung-hee’s military dictatorship?

Park Chung-hee took power in a 1961 coup and used martial law to silence dissent. He jailed hundreds of political opponents and activists until his death in 1979.

What was the significance of the Gwangju Uprising in 1980?

In 1980, General Chun Doo-hwan took power and extended martial law. His regime brutally suppressed student protests in Gwangju, killing hundreds. This event was a turning point in South Korea’s fight for democracy.

How did South Korea’s transition to democracy end the era of martial law?

The Sixth Republic in 1988 brought South Korea its first true democracy, ending martial law. Yet, martial law’s legacy still shapes the nation’s history and politics.